The Loop

Failure as System Design

A Lesson Learned

I was a young cavalry officer counting rations in a supply tent in Germany when Colonel Don Holder walked in. He commanded 8,000 soldiers—the last place I expected to see him was watching me inventory MREs in the field trains. He asked how I was doing. I said I’d rather be forward in a Bradley than in a tent counting boxes.

Holder was rail thin, taciturn, one of the Army’s leading operational thinkers who’d helped write the AirLand Battle doctrine. He looked at me and said in that deep voice with just a hint of Texas drawl: “I get it. But if you’re going to sit in my chair someday, you need to understand how all the battlefield operating systems work together. Keeping troops fed and fueled is what lets us cover ground when we’re moving forward in the attack.”

A year later, Colonel Holder and the 2nd Cavalry regiment led the coalition attack into Iraq. The lesson stuck: integrated systems win wars. But there’s a corollary Holder didn’t teach—one he learned when his father was killed commanding the 11th ACR in Vietnam: when operations continue to fail using the same strategies, there is a flaw in the system that perpetuates a bright shining lie and prevents challenges to the status quo.

I’ve spent the last few posts looking at the drug war and asking why, after fifty years and countless billions of dollars, we’re still fighting the wrong war with the wrong tools in the wrong places. The answer is simple: the system profits from failure. Contractors fund Congress, Congress funds contractors, programs fail, and failure generates more appropriations. That’s The Loop.

Follow the Money

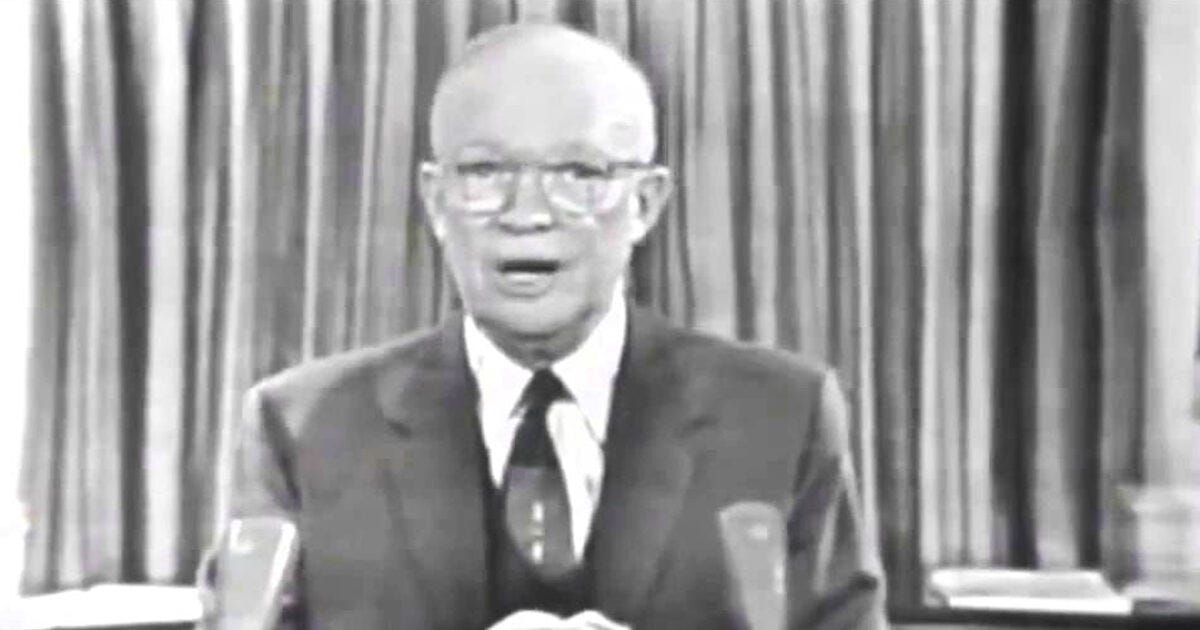

In his farewell address, President Eisenhower prophetically warned us against the influence of the military industrial complex. He warned us that, “We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together.”

Drive through Tyson’s Corner, Crystal City, or Pentagon City and you’ll see the manifestation of Eisenhower’s warning. The glass and steel towers are monuments to the explosion of federal spending and testimony that the core competency of federal contractors like General Dynamics, Booz Allen, and L3 is the ability to exploit the federal procurement processes to their advantage rather than to solve intractable problems facing the nation.

Why are we fifty years into the war on drugs and have made few, if any, significant inroads in addressing either the supply or demand side of the problem? The problem lies in three reinforcing failures: successive generations of leadership failures across both Republican and Democratic administrations, ineffective congressional oversight, and a defense industrial sector whose revenues are tied directly to government spending rather than performance and outcomes.

The Pattern Repeats

In his seminal work Dereliction of Duty, former national security adviser H.R. McMaster documented how military and civilian leaders in Vietnam served their own institutional interests rather than national interests. They knew the war was unwinnable. They reported progress anyway. Why? Because candor threatened budgets, careers, and contractor revenue.

The irony: McMaster himself became complicit in Afghanistan’s twenty-year failure using the same playbook he’d criticized. But that’s a different discussion for a different day.

The pattern applies identically to the war on drugs.

Institutional incentives reward continuation over candor. Failure generates the unquestioning continuation of strategy accompanied by expanding appropriations. Success would end the revenue stream.

They Knew and Did Nothing

We don’t need Daniel Ellsberg to expose institutional collusion in the drug war. The evidence has been documented and ignored by the executive branch and by Congress in real time.

In 2005, RAND Corporation published a comprehensive assessment: treatment is significantly more cost-effective than enforcement, interdiction has minimal impact, source country control doesn’t work. Seventy-four percent of Americans believed we were losing the drug war. Policy never changed.

The Government Accountability Office has been even more direct. In 2009: duplication and inefficiency. In 2016: “DOD and Congress cannot ensure the counterdrug program is achieving desired results.” In 2020: GAO added drug misuse to its High-Risk List, citing “challenges in sustained leadership and coordination.” In 2024: same problems, same failures, same waste.

Congress received these reports. Read them. Filed them. Appropriated more money anyway.

The Loop

Why would Congress continue funding programs documented to fail?

Follow the money.

Citizens United in 2010 made unlimited political spending “free speech.” The Supreme Court ruled five to four that corporations have First Amendment rights to spend unlimited amounts on political campaigns. The decision opened the floodgates to Super PACs and unlimited dark money in politics.

The result: contractors fund the committees that oversee them. Defense contractors spent $70 million lobbying in the first half of 2023 alone and contributed $3 million to Armed Services Committee members in just two quarters. Since 2003, the defense industry has spent $374 million on campaign contributions and $2.7 billion on lobbying. Private prison companies contributed over $4.4 million in the 2024 cycle, overwhelmingly to members who vote on criminal justice policy. The overseers are funded by the overseen.

The Loop works like this:

The Loop In Action:

In May 2020, General Dynamics was awarded a State Department IT services contract to “enhance counter-narcotic and anti-crime interdiction capabilities” for the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs. The contract promised to “deliver new technical capabilities to counter-narcotics trafficking” and “minimize the impact of international crime and illegal drugs.”

Four years later, overdose deaths reached 107,543 annually—the highest ever recorded. Did the program fail? By any measure of drug interdiction effectiveness, yes. GAO documented that DOD counterdrug programs “lack reliable performance measurement” and couldn’t demonstrate results.

Did General Dynamics lose the contract? No. The company has been “a mission-integrated partner with the State Department for more than 20 years.”

Follow the money: General Dynamics contributed over $205,000 to Armed Services Committee members in just the first two quarters of 2023. House Armed Services Ranking Member Adam Smith received $20,000—the highest amount from General Dynamics. Smith’s former chief of staff now serves as General Dynamics’ director of government relations, joining the company one month after leaving Smith’s office.

In 2023, General Dynamics spent $12.2 million on lobbying. The company contributed $3.4 million in the 2024 cycle. The counterdrug programs continued. The deaths continued. The contracts continued.

That’s The Loop.

Why does this work? Because solving the drug war ends the appropriations. The system is optimized to perpetuate failure. Failure is the business model.

Gerrymandering makes it worse. Safe seats eliminate electoral accountability. Incumbents serve donors, not constituents. The only threat is a primary challenge—which contractors can fund.

Holder’s Lesson Inverted

Colonel Holder taught me that integrated systems win wars. But there’s a corollary: when operations keep failing despite obvious fixes, look for who’s profiting from the failure.

The drug war fails because The Loop profits from failure. We have fifty years of documentation. We know what works. And 107,000 Americans die annually while Congress appropriates $44.5 billion to programs that don’t work—because the contractors who profit from failure fund the campaigns of the Congress members who vote for appropriations.

That’s The Loop.

It’s not a bug in the code.

It’s the design of the system.