Where Have You Gone Howard Baker?

Our Nation Turns Its Lonely Eyes to You

In 1974, a Republican senator asked a question that would bring down a Republican president. Today, no one from either party seems willing to ask hard questions when their own side is in power. What changed? And more importantly: can we get it back?

The Question

The question that changed everything was simple and direct: “What did the President know and when did he know it?”

With those words directed at White House Counsel John Dean during the televised Senate Watergate hearings, Senator Howard Baker began a process that would unravel the Nixon administration and force the nation’s 37th President to resign in disgrace.

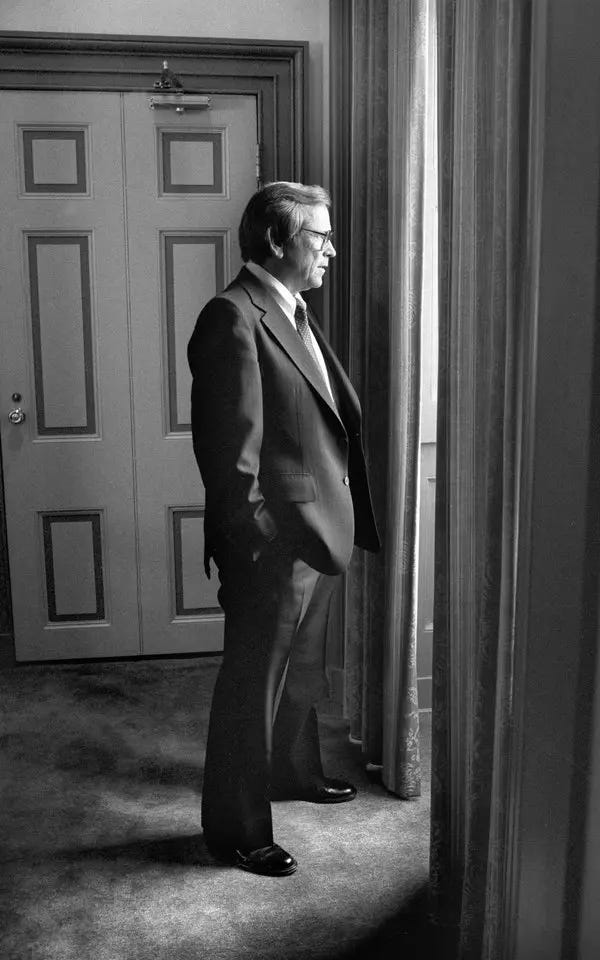

The Questioner

Senator Howard Baker, then 47 years old, was a moderate Republican from Tennessee and an unlikely star of the Watergate hearings. A Nixon ally, Baker entered the hearings skeptical that the investigation would lead anywhere and certainly never imagined that the inquiry would ultimately cause the resignation of the President. In his opening statement Baker asserted that the committee was “not in any way a partisan undertaking, but, rather it is a bipartisan search for the unvarnished truth.”

What made Baker remarkable wasn’t his ideology—he remained a conservative throughout his career. It was his understanding that democracy requires loyal opposition, not blind loyalty. He believed in smaller government and strong national defense, but he believed even more strongly that no person, not even the President, stood above the law. When the evidence pointed to presidential misconduct, Baker followed it—even though it meant political pain for his party.

The Watergate hearings, chaired by Senator Sam Ervin of North Carolina, were a model of bipartisan cooperation and sound governance. The criminal misbehavior uncovered by the committee as well as special prosecutor Leon Jaworski led to the imprisonment of numerous Nixon administration officials and ultimately the resignation of President Nixon.

Baker went on to serve as Senate Majority Leader, White House Chief of Staff under President Reagan, and Ambassador to Japan. His legacy—accountability to the rule of law and willingness to put country over party—makes him one of the most significant political leaders of the late 20th century.

The Baker Test

Let’s establish a clear standard for national leadership based on the behavior Senator Baker modeled:

Accountability Over Expediency: Do you hold your own party to established norms, or do you ignore misconduct when it’s politically inconvenient?

Opposition vs. Obstruction: Do you engage in spirited but constructive opposition, or do you obstruct governance itself?

Country Over Party: When forced to choose between political advantage and the national interest, which do you pick?

Fiscal Responsibility: Are you a responsible steward of taxpayer dollars, or do you spend recklessly when your party controls the purse?

Now let’s apply this test to both parties.

The Baker Test Case for Democrats: Bill Clinton

In 1998, Democrats faced their own Baker moment—and failed it spectacularly.

President Bill Clinton had an affair with a 22-year-old White House intern and lied about it under oath. The power imbalance alone—President of the United States and a young woman working for him—would get any CEO, university president, or military officer fired immediately and rightfully so. Add perjury, and it’s not a close call.

But Democrats circled the wagons and rallied to protect the embattled president. They parsed the meaning of “is.” They argued that lying about sex wasn’t impeachable. They attacked special prosecutor Kenneth Starr instead of addressing the underlying conduct of President Clinton. The Democrats prioritized keeping a politically successful president in power over holding him to basic standards of conduct.

The argument wasn’t that Clinton’s behavior was acceptable—it was that removing him would be politically costly and hand a victory to Republicans. Principle took a back seat to political calculation.

Howard Baker wouldn’t have done that. When faced with Nixon’s crimes, Baker asked, “What did the President know and when did he know it?” He followed the facts wherever they led, even when they led to his own party’s leader resigning in disgrace.

We need to ask ourselves: did Democrats’ defense of Clinton pave the way for Trump? If Democrats had held Clinton to the same standard we expect of CEOs, university presidents, and military officers—immediate removal for sexual misconduct with a subordinate—would Republicans have felt emboldened to defend far worse conduct two decades later?

The answer seems obvious. You can’t surrender principle when it’s convenient and expect to reclaim moral authority when you need it.

The Clinton precedent established a new rule: presidential misconduct is tolerable if your party controls enough votes to prevent removal. Character doesn’t matter. Abuse of power doesn’t matter. Only winning matters.

Republicans learned the lesson well. When they defended Trump through two impeachments, through January 6th, through classified documents at Mar-a-Lago, they were simply applying the standard Democrats established: protect your guy at all costs.

Democrats will protest: “That’s different! Trump’s conduct was worse!” Perhaps, but that’s not the point. The point is that once you establish that power trumps principle, you can’t complain when the other side adopts the same playbook.

Would the Trump era look different if Democrats had held Clinton accountable in 1998? We’ll never know. But we do know this: when you abandon standards for short-term political gain, you forfeit the moral authority to demand those standards from your opponents.

The Baker Test Case for Republicans

Would Senator Baker have turned a blind eye to the perpetrators responsible for January 6th, or would he have held them accountable? We know the answer—Baker would have done what Mike Pence and Liz Cheney did.

Pence, despite immense pressure from his own president and a mob chanting for his execution, certified the election results because the Constitution required it. That act of basic constitutional duty effectively ended his political career. He became a pariah in his own party for doing what every vice president before him had done without controversy.

Cheney investigated the facts, damn the political consequences. She asked the hard questions, just as Baker did with Watergate. She too was driven from office.

When a mob attacks the Capitol to prevent the peaceful transfer of power, there’s an assault on democracy that demands accountability. Pence and Cheney provided it. The Republican Party punished them for it. That’s the system we have now.

Would Senator Baker have confirmed blatantly unqualified nominees to serve as cabinet officers to satisfy the political aims of the administration? Would he have approved nominees with serious questions about their judgment on national security matters or credible allegations of misconduct and no relevant executive experience? Baker believed in competence and character. He voted for Reagan’s nominees because they were qualified, and he would have demanded the same standard from any administration. Political loyalty cannot substitute for professional competence when national security is at stake.

Would Senator Baker have supported tax cuts that added $3.4 trillion to the deficit without corresponding spending cuts to control federal spending? Baker voted for Reagan’s tax cuts—but he also voted for tax increases in 1982 when deficits spiraled. He understood that fiscal responsibility requires hard choices, not just popular ones. He knew that borrowing trillions to finance tax cuts while claiming to be fiscally conservative isn’t policy—it’s hypocrisy.

Where Are Today’s Howard Bakers?

The question isn’t whether principled leaders exist—it’s whether they can survive in today’s political environment.

When Mike Pence certified the election—performing the most basic constitutional duty of his office—he was booed at conservative conferences and effectively chased from presidential contention. His reward for four years of unwavering loyalty to Donald Trump, broken only once to follow the Constitution, was political exile.

When Liz Cheney and Adam Kinzinger held their own party accountable for January 6th, they were driven from office. When Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema resisted their party’s spending priorities, they became pariahs who ultimately left the Democratic Party. The system now punishes exactly the behavior Baker modeled.

Gerrymandering rewards extremism. Primary challenges target moderates. Social media amplifies outrage. Cable news profits from division. The structural incentives all point toward tribalism, not principled independence.

But incentives can change. Voters can reward courage instead of punishing it. Donors can fund principle instead of partisanship. Media can elevate substance over spectacle. The question is: will we?

The Choice Ahead

Our democracy faces a simple question: Do we still have leaders willing to do what Howard Baker did?

Not leaders who criticize the other party—that’s easy and profitable. Leaders willing to hold their own side accountable when it violates the norms that hold our system together. Leaders who understand that winning isn’t everything if you destroy the game in the process.

The stakes are higher now than in 1974. Nixon’s crimes were serious, but he never questioned the legitimacy of elections. He never incited violence against Congress. He never claimed absolute immunity from prosecution. The erosion of norms that began with Clinton’s defenders and accelerated under Trump’s enablers has brought us to a precipice where the fundamental underpinnings of the republic are at risk.

History will judge today’s leaders not by how much they won, but by what they preserved. Howard Baker chose principle over party when it mattered most. He asked the hard question even when he didn’t want to know the answer. He followed the facts even when they led somewhere painful.

That’s the standard. That’s the test.

The question isn’t whether your side has failed—both sides have. The question is whether anyone will choose differently when the next crisis comes. Because it’s coming. And when it does, we’ll discover whether we still have leaders who understand that democracy requires more than winning.

Our nation turns its lonely eyes to you, Howard Baker. But more importantly, we’re anxiously watching and waiting to see if anyone today has the courage to follow your example.