Why We Work Crashed and Netflix Built a Dynasty

Hoops, Fighter Jocks, and Left Hooks

“Cash is a fact. Profit is an opinion.”

For decades, NBA basketball was a plodding half-court game. Then Paul Westhead showed up with the 1980 Lakers and ran on every possession. His team won the championship. By 1981, Magic Johnson wanted him fired. The system was too rigid. Westhead wouldn’t listen, couldn’t adjust.

Pat Riley replaced him and added what Westhead wouldn’t: Kareem’s post game, defensive enforcers like Kurt Rambis and Michael Cooper, and the ability to slow down when winning required it. Riley’s Showtime Lakers won four championships because he embraced Westhead’s pace, combining it with championship discipline and relentless focus.

Phil Jackson refined it with the triangle. Popovich perfected it in San Antonio with “beautiful basketball.” Both won multiple championships because they could adjust.

Then Mike D’Antoni arrived in Phoenix with “Seven Seconds or Less.” Space the floor, get a shot up before the defense can set, attack before they can organize. D’Antoni’s Suns ran at game speed, forcing defenses to react. Phoenix averaged 110 points per game and revolutionized pace and spacing.

They also gave up 107 points per game and never made the Finals.

D’Antoni rediscovered on the basketball court what John Boyd figured out decades earlier in fighter jets. Boyd was an Air Force pilot who revolutionized combat theory with the OODA loop (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act). His work became the foundation for AirLand Battle doctrine. When General Norman Schwarzkopf commanded allied forces during the Gulf War, his planners used Boyd’s tenets: force the enemy to react to you and keep them off guard. Major General Barry McCaffrey’s 24th Infantry Division drove 230 miles through the Iraqi desert in less than four days, swinging wide around the Iraqi flank while they were still trying to figure out where the main attack would come from. The left hook cut off every retreat route, caught the Republican Guard completely by surprise, and destroyed them before they could reorient.

Boyd wasn’t teaching speed for speed’s sake. He was teaching tempo as a weapon. D’Antoni’s Suns executed this perfectly on offense. The principle was sound.

Phoenix, Game 6, 2006 Western Conference Finals. The Suns score 40 points in the first quarter. They’re up 18 in the second. Then Dallas amped up their defense and locked down the potent Suns offense, holding them to 36 points in the second half. Mavericks win 102-93. Series over.

D’Antoni’s answer to criticism was always “the offense will outscore the problem.” He wouldn’t compromise the system because that would admit the approach was incomplete. He was optimizing to prove his system worked, not to win championships. D’Antoni was listening to Boyd on one side of the ball and ignoring him on the other. Steve Kerr and the Golden State Warriors proved you have to do both.

Kerr’s Synthesis

Steve Kerr played for Jackson and Popovich. He watched D’Antoni revolutionize offense. He synthesized it all.

From D’Antoni: pace, spacing, threes. From Popovich: ball movement. From Jackson: defensive discipline and the willingness to slow down when winning requires it.

The Warriors ran the second-fastest pace in the NBA but finished top five in defense. They could adjust.

Result: Four championships.

The same principle applies in business. Speed matters, but only if you can adjust continually to keep the competition from figuring out your next move and getting there first.

WeWork and Netflix

WeWork was D’Antoni’s Suns. Netflix was Kerr’s Warriors.

WeWork optimized for speed. They blitzed the market, signed leases faster than anyone, scaled to 800 locations. The system worked exactly as designed. Membership growth exploded. Valuation hit $47 billion.

But they had the wrong North Star. WeWork optimized for the story they wanted investors to believe, not the cash reality sitting on the balance sheet. Cash is a fact. Profit is an opinion. And when you optimize for the opinion, you eventually collide with the fact.

WeWork locked into long-term lease obligations while customers signed short-term contracts. When growth slowed, the mismatch detonated. The IPO collapsed. Founder Adam Neumann was forced out. The company laid off thousands and the valuation cratered 90%. The problems went deeper than the business model. Self-dealing, conflicts of interest, and governance failures compounded the fundamental flaw. In business, everything can look great right up until the moment you run out of cash.

Netflix started with the same pace obsession. DVD by mail, fast growth, prove the model works. Then they saw streaming coming and pivoted. They could have defended the DVD business. They didn’t. They optimized for winning the future, not for proving their current system was right.

They could have remained a distribution platform. They didn’t. They invested in the best creators to control the end-to-end entertainment experience. Each pivot looked like abandoning what made them successful. Each pivot was actually staying true to their North Star: own the customer’s entertainment experience completely and optimize lifetime subscriber revenue.

Netflix adjusted. WeWork didn’t. One built a dynasty. One ended in the conference finals.

The ScorecardQuick test: Can your team explain in one sentence how their work moves the North Star?

If no → Wrong Scorecard.

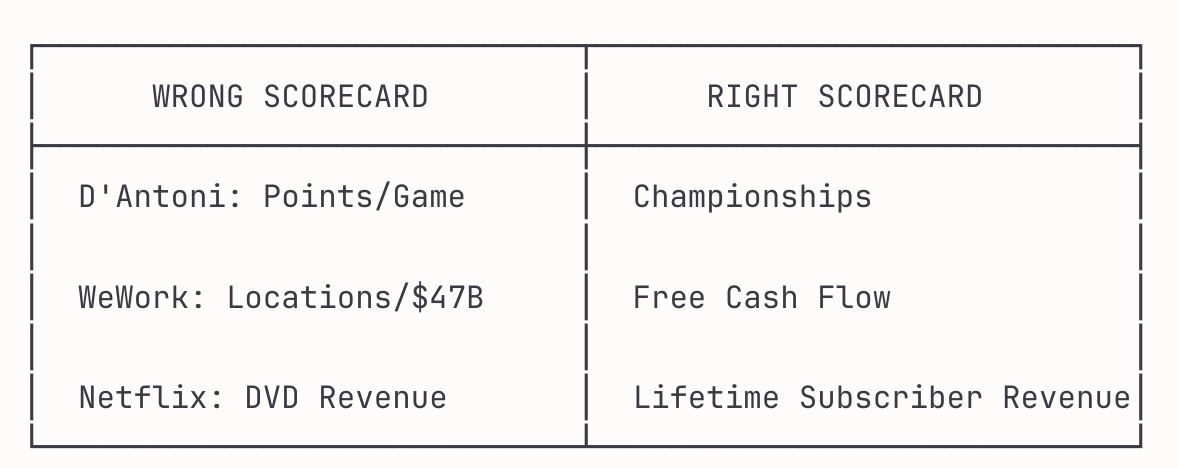

D’Antoni measured offensive efficiency. The Suns led the league in points per game. His scorecard said the system worked.

The championship scorecard, the only scorecard that matters, says otherwise: Conference Finals appearances: Two. NBA Finals appearances: Zero. Championships: Zero.

WeWork measured growth velocity. They hit 800 locations, $47 billion valuation. Their scorecard said the model worked.

The cash flow scorecard said: Long-term lease obligations: $47 billion. Short-term customer contracts: Mismatched. Viable business: No.

Netflix measured customer control. When they didn’t own streaming, they built it. When they didn’t own content, they invested in the best creators. Their scorecard kept asking: Do we own the customer’s entertainment experience end to end?

The dynasty scorecard said: Market cap: $400 billion+. Competitors: Marginalized

Every organization on every playing field has a scorecard. The challenge is to measure what matters. Measuring activity alone is inadequate.

Are physicians measured and rewarded for procedures delivered or patient outcomes?

Is the DEA measured and rewarded for kilos confiscated or decline in overdose deaths?

Are universities measured and rewarded for test scores or whether graduates can actually do the job?

Are police departments measured and rewarded for arrests made or whether the neighborhood is safer?

Are representatives optimizing for re-election or substantive legislative accomplishments?

Your organization has a scorecard right now. The question is whether it’s measuring and rewarding what actually wins, or what makes your current approach look good.

D’Antoni’s offense was brilliant. It just wasn’t built to win championships.

WeWork’s growth was real. It just wasn’t built to survive.

Netflix kept pivoting because their scorecard measured the right thing.

Ask yourself: What’s on yours?

Is our organization WeWork or Netflix? Are we the Suns or the Warriors?